Guest Post by Natalie Kwadrans

As I sat at home this weekend, knowing the hearing at the Canadian House of Commons was starting today regarding the newly proposed Canadian Breast Cancer Screening Guidelines, I felt the need to tangibly highlight to others why I feel these guidelines fail women in this country.

So, I did what any other bored de novo stage 4 breast cancer patient would do. I decided to read through and compare the Canadian Task Force on Preventative Health Care’s 2024 Proposed Breast Cancer Screening Guidelines scientific references to the newly revised US Task Force on Preventative Services’ 2024 Breast Cancer Screening Guidelines and its scientific bibliography.

For background, the Canadian Task Force has resisted calls for change, with its draft recommendations holding firm that routine breast screening should not begin until age 50 in Canada.

I was curious to dig deeper because the US felt there was enough new evidence to change their breast cancer screening guidelines to start at 40 instead of 50. Ten of the thirteen Canadian jurisdictions also felt the same, and changed their guidelines to begin screening at 40, with the exception of Alberta, which dropped their screening age to 45.

So, what did the US and then of the thirteen Canadian jurisdictions know that the Canadian Task Force didn’t?

I figured the answers would lie in the research they used to inform each Task Force’s recommendations. I was right. It was disheartening and downright maddening.

I created a spreadsheet to compare the sources each Task Force used and did a high-level analysis of the research simply by reviewing the titles. Therefore, it’s not a perfect analysis. I was trying to see what new research was being used by the Canadian Task Force. I was extremely disappointed and let down by the content, as what the Canadian Task Force used wasn’t reflective the scientific evidence that is currently available. And that lack of attention to recent research will, in my opinion, come at the expense of Canadian women’s lives.

Based on this Twitter post from July 31, 2023, The Canadian Task Force preferred to ask “the masses” do the legwork for them. I’m not sure why the Federal Government paid $500,000 of tax payer money to expedite the guidelines. What I determined from my analysis is that 41% of the Task Force sources cited in the draft recommendtions included data from before the year 2000!

The image in this blog shows a quick side-by-side comparison between the two Task Forces’ bibliography. It is clear that not all research is equal.

After doing this analysis, three things stand out to me

- 41% of the research used by the Canadian Task Force predates the year 2000;

- 23% of the research listed re-uses the same original data, so the results will obviously skew to the data being reused. What is worse, is they are using a discredited study, the Canadian National Breast Screening Study, or CNBSS for short, from the 1980s;

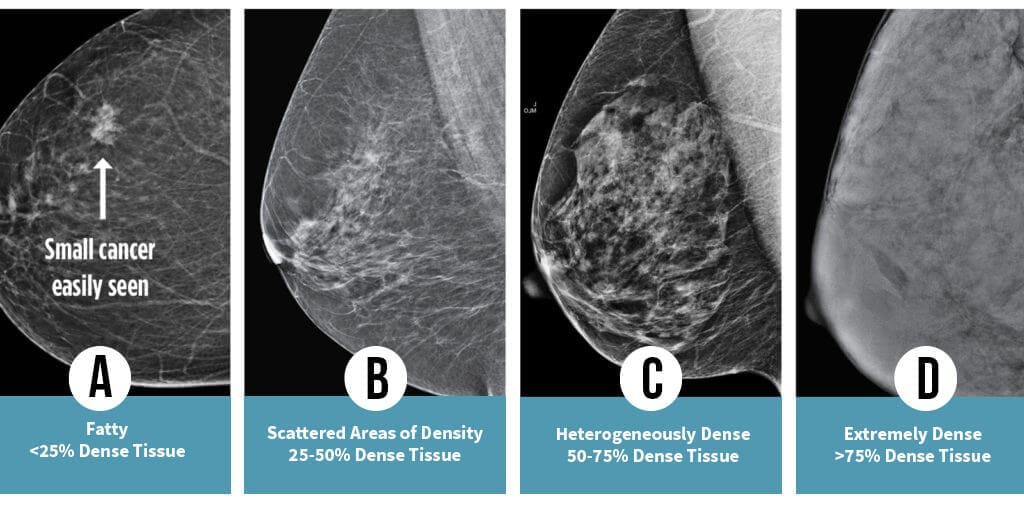

- there was very little research included on breast density and race/ ethnicity.

Do you want to see the two bibliographies for yourself? Here is a link to my spreadsheet, as well as a short video that explains my document.

Natalie Kwadrans has been an advocate for cancer patients since she was diagnosed with de novo, triple-positive breast cancer in 2019. She is a patient advocate with Dense Breasts Canada, a patient partner with the Canadian Society of Breast Imaging and a Terry Fox Ambassador and a Patient Representative for Marathon of Hope Cancer Centre’s Network (MOHCCN).

Natalie completed a BSc, though she altered course to compete as a snowboard racer for Team Canada. She then pursued graduate-level studies in business and, over her two-decade long career, broke down cross-organizational silos to implement customer-centric strategies. She was a sessional Bachelor of Business (BBA) instructor at three universities and holds Project Management Professional, Certified Public Accountant and Certified Management Accountant designations. Halfway through her MSc from HEC Paris she was diagnosed with cancer. Her ongoing palliative treatments forced Natalie to quit her career and studies.